- An Unexpected Habour

- Addicted to Painting

- Unveiling Confusing Encoded Symb

- Dissociate (Extracted)

- Huang Du‘s Interviews with Wang

- Feeling History in Cultural Tour

- Empty Layer, Split and Transpare

- Art in Restrictions

- Cultural Fusion in the Informati

- Tthe Crisis of Faith

- Unruly Ants

- Wang Xiaosong Colour

- We Live in Illusions Genuinely

- Inheritance and Development

Thorsten Rodiek

is not the eternal Way.

The name that can be named

Is not the eternal name.

The nameless is the beginning of Heaven and Earth.

The named is the mother of all things.

Therefore: / Free from desire you see the mystery.

Full of desire you see the manifestations.

These two have the same origin

But differ in name.

That is the secret,

The secret of secrets,

The gate to all mysteries. --Lao Tzu, Tao Te Ching

Xiaosong participated in the Venice Biennale in the summer of 2011. He did not exhibit his work Making Life , which was specifically created for the Biennale, in the official Chinese pavilion, but rather presented it together with the works of twelve colleagues at the Convento dello Santo Spirito, now serving as a school, where the Venice Biennale Collateral Event with the informative title "Cracked Culture" was organized. (fig. 1)

Making Life consists of a steel cable of 75 meters length, of 18 more cables twisted and wrapped around each other, and of some 500,000 small, individually manufactured, red, human figurines. This installation was attached to two opposite walls, sagging to the ground in between. News broadcasts from different information media were simultaneously sounded from 36 loudspeakers.

This is how Xiaosong described his work: ”They [the figures] have been tied closely to the rope cable, become muddled up, and symbolize both those who rule and have interests as well as those who are at a loss, the indifferent populace and disadvantaged groups. I would compare them to grasshoppers on a rope.“ By way of criticizing the media the artist added: ”A lie repeated a thousand times becomes a truth. In terms of their essence there is no difference between CCTV [the Chinese news channel] and CNN,“ and he went on that there were more than a few people, who ”gradually turn into partisans and accomplices for the sake of a mini profit.“ Xiaosong also critically commented the situation of artists and the general situation in China on German television.

These were and are clear statements from an artist, who in his role as a painter is both a professor at the art college in his native city Hangzhou as well as being able to record considerable exhibition successes and sales of artworks in the Asian region.

It is needless to say that this requires great courage.

Beside his activities as a painter, Xiaosong has an architecture firm in Hangzhou together with the Berlin architect Peter Ruge. They have planned, organized, and realized several new buildings and urban landscapes. Although Xiaosong has no formal training as an architect, his feeling for design and spaces enables him to develop urban squares and building facades in close cooperation with the architect.

These activities ultimately inform his paintings, which are much rather to be regarded as three-dimensional pictorial objects, than as mere two-dimensional pictures of a more traditional style.

With these diverse activities it is therefore only consistent that Xiaosong also created a series of video films, which are a critical analysis dealing in a very subtle way with the present political situation in his native country China.

At the same time, Xiaosong is a wanderer between the (artistic) worlds. Not only did he study for a while at the Berlin University of the Arts, where he met his now wife, a music teacher from Japan, but his art also unites cultural achievements of the East with those of the West.

Not only is Xiaosong a trained painter and adept of traditional Chinese calligraphy, but he is also intimately familiar with all Western artistic trends and theories of the past and the present.

The following passages are intended to demon-strate how Xiaosong blends the Chinese tradition and way of thinking with impulses from Western modernity to create a very special and individual way of painting, which ultimately not only convinces in terms of aesthetics but can also be interpreted in terms of politically engaged, critical art. The subtitle of this essay is an indication of this.

Oil painting is a relatively young tradition in China, and it bases exclusively on the knowledge of Western painting. Today, contemporary Chinese artists nevertheless use oil painting as a matter of course. But beside oil painting, the education in calligraphy is still an integral part of Chinese academy art studies. It should therefore be borne in mind, that a majority of today’s Chinese artists still exclusively create calligraphies, which are always measured against the greatness of the millennia-old tradition of painting. Due to the particularities of this profession, however, this procedure completely precludes any form of reference to or representation of current events.

Oil painters are presumably a minority in China, even though they apparently set the tone both in the Western perception and on the inteational art market today. This painting technique, which clearly originates from the West, saw its beginnings in China under Mao, in the so-called Socialist Realism and under the influence of Soviet propagandist art. Today, this type of definite, artistico-political determination has been principally abandoned, at least when it comes to free, non-public works. For this reason, there are at present very many completely different trends, styles, and forms of presentation in China: at times apolitical, at others political, and sometimes conformist.

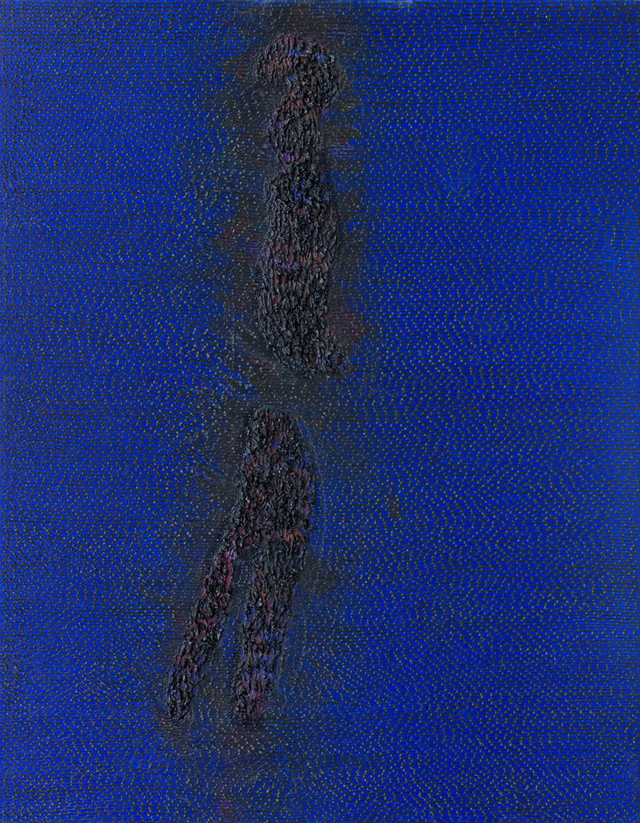

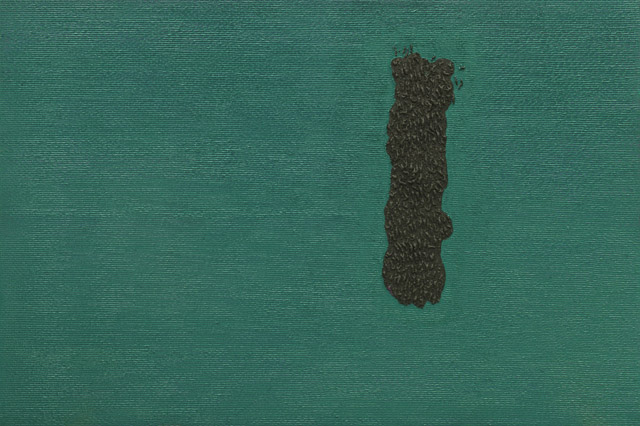

Xiaosong’s pictures are usually in essence monochrome, displaying luminous, glowing colors, which may range from yellow to red, green, and blue to an intensive purple. In his latest works, however, he has been modifying this by using second or third colors, but there is always one dominant main color that essentially sets the basic tone or the mood of a painting. (cat. 006)

At the first, superficial glance, Xiaosong’s pictures are reminiscent of works such as those by Yves Klein, by the American Hard-edge painter Ellsworth Kelly, or of Barnett Newman’s meditative large-format paintings or of those by the Italian painter Lucio Fontana with their slashed canvases.

It is obvious that these eminent Western painters have inspired Xiaosong. He himself emphasizes the great influence of Paul Klee’s works on his own. It was there that he encountered the combination of abstraction and realism that he has always been interested in. This refers in principle to the paintings Klee created during his famous trip to Turin. (fig. 2)

Beside other influences, it was also Klee‘s art that made Xiaosong receptive for the scriptural elements spreading carpet-like over the entire image area and frequently structuring his pictures. (fig. 3)

A more detailed observation, however, reveals very essential differences in terms of form, technique, and contents as compared to the above-mentioned representatives of monochromy.

Xiaosong’s latest paintings are not traditional, two-dimensional pictures in the conventional sense, but rather three-dimensional pictorial objects or picture boxes, each with a depth of 8 cm. Sometimes, canvases are used as image carriers, but often epoxy resin panels, onto the hard and smooth surfaces of which the paint can be gradually applied in many layers and lengthy work steps, resulting in a pasty surface texture that creates shiny, light-reflecting high reliefs. The texture of these pictures becomes vital, unsettled, and exuberantly bubbly.

In the centers of some of these pictorial objects are wide, vertically arranged openings, which allow the observer to look inside of the image carrier, where there are sometimes photos of pin-up girls from magazines, comics, or the like to be discovered. Some of the pictures may be irregularly perforated in different places, admitting the view of the dark hollow behind it.

In comparison to the monochrome overall appearance of the picture, these ”holes“ are shock-like contrasts. They are a visually dark accent, which on the one hand exerts a dangerous pull, and on the other hand has a definite erotic quality. It all remains ambivalent.

The same applies to the relief-like painting itself. On close examination of the image area, it becomes evident that we are by no means dealing with purely abstract art in the sense of Tachisme or Art Informel, because there are innumerable, each complete and individually formed human bodies or perhaps bodies of ants, which are bustling and swirling around.

It cannot be definitely ascertained whether these are being pulled into the big opening as into an infernal, gaping gullet, or whether they are being pressed out as in a birth process.

Again we meet with the ambivalence that is so characteristic of Xiaosong’s works.

A further ambiguity arises from the contrary im-pressions resulting from looking at the pictures from a distance first and then looking at them from close up.

Seen from a distance, the monochrome color appears to be perfectly uniform. According to the respective color tone, associations of fire, the sun, water, or flower fields are triggered. At the same time, all of the works have a strongly meditative character. The color in its perception as light and as mood creator, but also as three-dimensional carrier of effects with its respective features, is initially the only content.

In opposition to that impression stand the innumerable, twirling bodies, which can be observed from close up and which create the relief-profiled, irregular, dynamic surface structures.

To the attentive observer, these pictorial dynamics themselves are even continued by the character of the overall picture changing considerably in different light conditions according to the time of the day. This effect is caused by the significant amounts of preciously shining oil paint, which Xiaosong applies over a period of many workdays in uncounted layers and in a very pasty texture. Only these layers of paint can produce the intense light reflections as well as the dynamics inherent in all the works and the tension immanent in the picture that the observer perceives.

Color for Xiaosong therefore is not only a visual medium, which can achieve different moods through different colors, but it is also a haptic medium. The color is both designed itself and a designing element in that it forms the relief of the entire picture, thus acquiring a material and textural quality.

The dark and largely empty hollow space underneath is in stark contrast to the painted surface.

For this purpose, it is informative to take another look at a work by the above-mentioned Italian painter and sculptor Lucio Fontana. A good example is the Concetto spaziale, Attesa (Spatial Concept, Expectation) from 1965. (fig. 4)

Fontana wanted to free painting from its traditional, apparently static two-dimensionality and open it spatially. He did this by slashing the canvases and cutting openings into them. In this way he wanted to realize his objective of dynamic plasticity. At the same time, Fontana was convinced that static painting had come to an end and should be replaced by dynamic art from then on. In the works of both painters, Fontana and Xiaosong, we can find the irregular, differently shaped perforations in the monochrome and brightly colored painting surface. (fig. 5) Fontana’s pictures also have the same kind of openings with the heavily encrusted paint surface, which intentionally evoke erotic associations. (fig. 6)

Xiaosong’s works coincide with Fontana’s both in terms of their monochromy as well as the three-dimensional openings in the center of some of his pictures. But, as already mentioned, the works differ in that some of Xiaosong’s pictures are not simply slashed like Fontana’s, but open up into (pictorial) spaces, some of which are designed, and which are actually formed by boxes behind the surfaces. In a way, Xiaosong implemented Fontana’s spatial concept more consistently. This also applies to the dynamics Fontana strived for.

But this was not Xiaosong’s principal aim. Other than Fontana, who never used figures in his pictures, Xiaosong’s figures counteract the dominating monochromy, which otherwise serves to unify and harmonize the pictures in a special manner.

But perhaps it was a different artist altogether who inspired Xiaosong to place the vagina-shaped opening in the center of some of his works, thus including the thematic complex of birth and death: the French realist Gustave Courbet.

His picture from 1866 L’Origine du monde (The Origin of the World), which today is at the Museé d’Orsay in Paris, had remained undisclosed for reasons of alleged obscenity for many decades, and was first publicly displayed in 1988. It looks into the entirely naturalistic representation of the female genital in such a direct manner that it is capable of baffling or shocking even today’s viewers, especially when considering its revolutionary content with respect to the time of creation. (fig. 7)

As with Courbet, Xiaosong’s works also involve a sort of (female) dual nature or an additional ambivalence: on the one hand, the opening is the place of sexual desire and penetration, on the other hand it is that of birth or creation.

Their actual origin is and always will be the female womb.

In all probability, and particularly with regard to the mass depictions of the human body, Chinese art works have also been important sources of inspiration for Xiaosong.

It is in the district of Weicheng near the city of Xianyang, 20 km north of the province capital Xi’an on the Wei He River. The Mausoleum of Han Yang Ling holds the tomb of Han Jing Di (188–141 BC), the fourth emperor of the Western Han Dynasty.

Far from being completely excavated until today, thousands of doll-like, smaller than life-size human figures and animal sculptures have already been found there. These sculptures and figures represented the entire royal court of the Emperor Jingdi of Han. Today these figures appear slightly unreal, as their original colored clothing and their wooden arms have decayed, leaving only the clay torsi, although some of these have retained their colors. (fig. 8)

Very clearly inspired by these special tomb figurines, his latest pictures show large-format, differently colored, shadow-like depictions of larger human bodies or body parts, which are in turn occasionally populated by the small human figures. There are also entirely monochrome pictures, where the small figures are so densely packed in some spots that they in turn become large-format figures or body parts. The outlines of these larger formations clearly refer to the above-mentioned doll-like bodies from the emperor’s grave. Due to the monochrome composition, these contours are however only gradually revealed on detailed examination. (cat. 037)

In the 42 Buddhist caves and 210 niches of Yün-kang, a UNESCO World Cultural Heritage Site, there are more than 51,000 Buddha statues from the time between the years of 465 and 525 AD. The amassed arrangement and style of these stone-carved relief figures represent the various mythic manifestations of Buddha as the past, present, and future Buddha. They also show scenes from the life of Siddhartha and portraits of their donors. (fig. 9)

Although Xiaosong’s art has no religious references, such solutions and engagements of ancient Chinese culture with the representation of people as a crowd or as religious figures also inspired Xiaosong’s artistic development.

After the artistic upheavals in 20th century Western culture, today’s viewers take the lack of central perspective nearly for granted.

In Xiaosong’s works we encounter a large, two-dimensional plane with the relief figures in the foreground, which only admit a visual leap into the dark depths of the object through sudden pictorial openings in the center of some of the works. In these depths we can discern either a new, planar, and completely different picture, or merely a dark space.

This is the case particularly with the very recent pictures.

Constructivist elements such as colored strips or geometric, colored surfaces within grid-shaped, yet irregular patterns suddenly emerge and are arranged in suspenseful opposition to organoid, peanut-shaped forms. Floating like islands in a gigantic ocean, these pictorial elements are filled with human bodies.

For Xiaosong, these textured, tissue-like structures with infinite space behind them symbolize the regularity of everyday life with its minor, but continuous changes.

Organic and occasionally constructive elements seem to fluctuate freely as antithetic existential patterns before the immense, infinite matrix of time and space. (cat.049)

Scattered unevenly across the image area in darker colors within an irregular web pattern, another picture depicts a skull as well as a male and a female genital. In this manner, the antithesis between spirit and body, between abstract thought and physical nature, are artistically and concisely condensed to an existentially elementary entity. (cat. 055)

Without using a second color for accentuation, the artist has furthermore created paintings, in which innumerable individual bodies condense to form large, human figures or heads.

In his most recent paintings, we not always find human bodies formed of pasty oil paint populating the image areas. In some works, these human forms are instead replaced by ants or scriptural symbols reminiscent of Chinese characters. These are, however, purely inventive, script-like elements. The elements also form a sort of endless, ultimately uninterpretable, unexplainable, and inscrutable matrix as an unknown basis of all being.

It was the kernel, i.e. the core of a computer operating system defining the process and data organization, that inspired Xiaosong to these elements. All other software is based on the kernel, which quasi forms the basis for the layers of the computer’s inner life. A computer crash may lead to the screen displaying merely an apparently absurd, completely unintelligible combination of characters and digits.

The fact of Xiaosong’s education in calligraphy in China prior to his studies at the Berlin University of Art has already been mentioned. This certainly has a decisive influence on his pictures, and the scriptural features are very distinct in his surface designs. (fig. 10)

A third decisive influence that was to determine his style was a trip to the famous Alhambra in Granada, a World Cultural Heritage Site, which has an altogether emblematic character.

It was the first time for him to see the stucco of the Nasrid architecture from the time of the Moors. The lavishly and artfully braided patterns of texts, arabesques, tendrils, and leaves, Kufic and Nashki scripts decorating the Sultan’s palace inspired Xiaosong to compose his pictures with a relief surface structure and to connect various scriptural and figurative elements three-dimensionally. (cat. 062, fig. 11).

Even the colored strips or the square, green perforations he uses in his latest pictures are obviously inspired by the braided interlacings of the Moorish faience mosaics or the plasterwork grid structure of the Alhambra. (cat. 051, fig. 12).

Their spatial presence evidently bears witness to an entirely new development in his works, which show superimposed, rectangular discs filled with human bodies and behind them a light source illuminating the remaining, large-format image area. (cat. 047) This light as an immaterial phenomenon points at a primordial space, existing behind the human figures or behind the world, that becomes visible, but not immediately tangible or comprehensible. Underneath the real space of the picture or its surface, there is apparently another, energetic power, which can in general terms be interpreted as creative power. With regard to Xiaosong being Chinese, this can be taken as a visualization of the power of Dao (the Way).

In Daoistic Chinese philosophy Dao refers to an eternal active or creative principle, on which the origin of unity, of duality, and of the world of all things is based.

This ultimately results in the opposition of abundance created by the colored human bodies on the surface of the painting and the exactly centrally located dark openings or the occasionally nearly deserted, grid-like surfaces of some pictures. While in some works the inside is a calm anchor with the surroundings seeming vital and turbulent in contrast, in the other works the filigree, densely populated, floating elements form contrasts with the vast, web textured surfaces.

“My works presents a two-layer concept, both the inner and the external. The two-layer or multi-layer oppose each other and cannot be unified. The concept empty-layer is called empty when the framework is made. A layer in such paintings becomes carrier for cultural thoughts and spiritual consciousness. I compare my painting’s first-layer space to an criticism of deconstructive symbols, while the second layer, a layer of organic existence, is believed to be a collection of realist constituent elements…My realist paintings strive to create contradicitions and conflicts in the same space.”

In this manner, the artist succeeds in connecting realism as well as abstraction in terms of contents and artistic expression and in all their polarity on a new level, much like his model Klee once managed to do in a different manner.

The contradiction herein reminds us of Lao Tzu’s famous allegory of the wheel, when he illustrates the essence of Daoism:

The hole in the middle makes it useful.

Mold clay into a bowl.

The empty space makes it useful.

Cut doors and windows for the house.

The holes make it useful.

Therefore, the value comes from what is there,

But the use comes from what is not there.

According to Daoism, the hub of a wheel is the central empty space, which all else refers to and around which all else revolves. As the center is empty and static, it acts as calm anchor, guaranteeing the movement’s balance and stability.

For Xiaosong, life emerges from the center, from the (spiritual) void, and also returns there.

Both water as well as the nourishing root are equated with the female:

The rule according to the Dao, the rule according to the female strategy, will remain constant. It will be of constant presence, supported by the empty hub, the concealed root, the deep water, which means by the non-presence in its center as “present origin.“

It is evident that Xiaosong has consequently followed his own artistic path and will certainly continue to do so. Despite all changes in his recent pictures, the painter consistently adheres to his artistic and intellectual ideas, and at the same time he continues to strive for becoming more and more explicit in articulating the opposing phenomena of emptiness or the void and abundance, of abstraction and figuration, of space and surface.

This alone renders his work an absolute singularity within contemporary artistic creation.

Added to this are the inter-ethnic tensions between the different peoples living in China.

“Are we prepared to accept the values of the Enlightenment in China? No, even centuries after the age of Enlightenment the Chinese are not willing to accept them. In this sense it is interesting that the exhibition takes place here, of all places. For the current situation in China is absolutely crazy. If I had to give a name to this epoch, then I would say, we live in an Age of Madness.“

It is significant in this context that by his own admission Xiaosong intensely engaged himself with the essay Avant-Garde and Kitsch, published as early as 1939, by the American art critic and icon Clement Greenberg—himself at that time a Trotskyist. In it, Greenberg intended to determine the role and purpose of modern art in a society such as the socialist totalitarianism in the Soviet Union of that time. In light of today’s balance of powers in China, which still define themselves as communist, Xiaosong’s interest in this special essay by Greenberg becomes understandable, because it helps him to define his own artistic position in relation to what is officially supported and propagandized.

According to Greenberg, in order to have its ideology take effect in the realm of arts, a totalitarian regime needs to accommodate mass taste, which craves for distraction. Thus, such art inevitably approximates kitsch, which is defined by Greenberg as follows:

Dictators such as Hitler, Stalin, or Mussolini availed themselves of this art of kitsch in order to please the mass taste. Greenberg saw the counterpart in the continuous development of art by the avant-garde. Ultimately, this art would then however turn into mere l’art pour l’art in that it no longer deals with contents or topics, but exclusively focuses on purely artistic means. In the process, it would abandon political and/or social issues.

Xiaosong evades the risk of such an absolutization by including the achievements of the avant-garde as an indispensable part of his artistic creation on the one hand, and by adopting a socio-political stand in his pictures on the other hand. He repeatedly points out the problem of the crowd and overpopulation.

A good example of this is the series “Unruly Ants“ (cat. 020), consisting of 250 individual pictures, which questions the present situation in China with critical irony in its title. And he also demonstrates that despite all measures of state control, freedom always finds loopholes. His works containing crosses—by no means in a Christian religious sense—visualize, by their slanted position and the axial displacement, the fact that there are no longer any common social goals in today’s Chinese culture, no common consensus, and no overall, connecting, elementary concepts of a positively connoted entirety. (cat. 044)

According to Xiaosong’s view, everything is drifting apart, as in his paintings.

He illustrates all of this in an artistic style that is beyond all topical, day-to-day political events by visualizing very basic or general problems and threats, which are valid far beyond the present and reach into the future, i.e. which are timeless. His art does not only apply to his own country, China, but rather describes a general worldwide phenomenon that relates to humankind as a whole.

And this is exactly what it takes to become a true classic, even if he regards his own country as a sort of volcano or as a pot ready to blow its lid off: that is, as a nation of unruly or unrulableants.